Quand la nature et l'humanité se rencontrent, il en sort un roman étrange et puissant, grondant et poétique, profondément ancré dans des paysages sauvages et préservés, sublimés par la plume d'un écrivain au plus près des émotions et des mots.

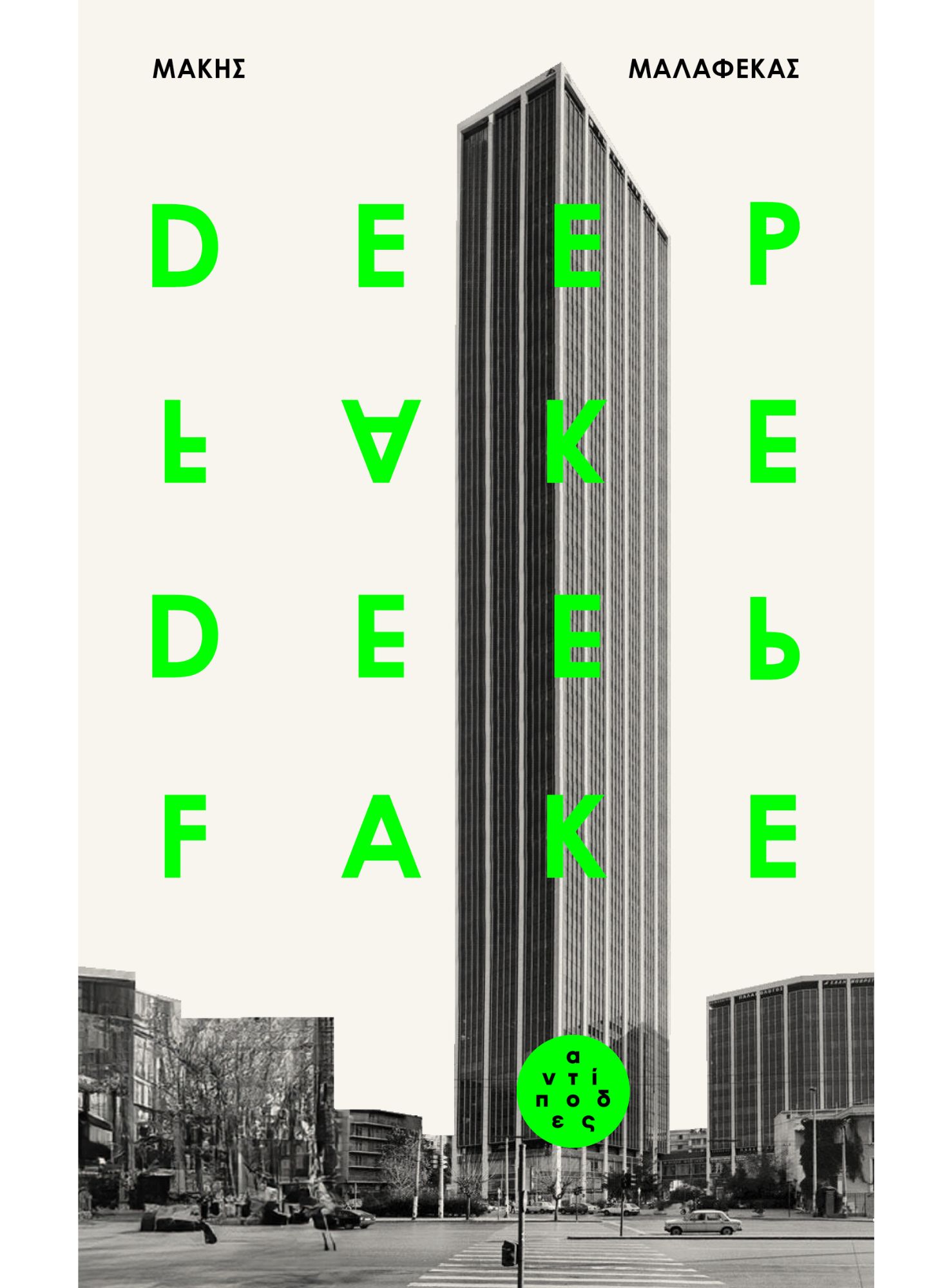

Nominé pour l'édition 2025 de l'EUPL, Prix de Littérature de l'Union Européenne, l'écrivain grec Makis Malafékas se prête au jeu d'un entretien "coulisses" autour de son écriture et de ses inspirations. Né à Athènes en 1977, il incarne un nouveau visage de la littérature grecque contemporaine. Makis Malafékas s’est imposé sur la scène littéraire avec ses romans noirs, dans lesquels il explore les mutations de la société grecque à travers le regard acéré de son alter ego Mikhalis Krokos. Son écriture, marquée par l’humour, le chaos narratif et une forte inspiration internationale, interroge la réalité urbaine et l’identité contemporaine. Traduit en français, il révèle à travers des œuvres comme "Dans les règles de l’art" (éditions Asphalte) et Deepfake une Athènes oscillant entre polar social et aventure romanesque.

Vous avez étudié l’art. Cette première passion nourrit-elle votre écriture ?

Absolument, les deux passions se sont développées côte à côte et ont indéniablement dialogué. J’ai souvent eu cette démarche, que ce soit devant une œuvre visuelle ou en littérature : « Comment ont-ils fait ? » Dans sa dimension concrète et technique, comment l’artiste a-t-il éveillé en moi une émotion précise ? En cherchant à répondre à cette question, j’ai commencé à percer les secrets du métier d’écrivain.

D’où naît l’inspiration ? Quel est le déclencheur d’une histoire ? Prenez-vous beaucoup de notes ?

Non, je ne note jamais rien. Mon approche est assez originale : j’écris dans un seul jet – le premier est aussi le dernier. L’histoire mûrit et s’élabore entièrement dans ma tête ; je m’en souviens sans mal et je corrige rarement. En général, tout démarre d’une idée toute simple, un événement étrange qui frappe le héros. À partir de là, tout se déroule, avec pour principe que je sais (ou finirai par apprendre par le repérage) comment tourne ce monde.

Quand vous imaginez une nouvelle histoire, ce qui vient en premier, ce sont les thèmes ou les personnages ?

Le personnage central est toujours un alter ego assumé : c’est un écrivain qui tente de faire publier le livre que je viens d’achever. Il lui arrive des ennuis, et cela pose la base de mon livre actuel (et de son prochain). Donc, ce sont bel et bien les personnages qui précèdent. Le thème doit être ce qui l’arrache à son cocon urbain, pas forcément confortable — mais tout de même un refuge. D’une certaine façon, le « thème », c’est le monde où il évolue.

Comment gérez-vous la structure du récit ? Pourriez-vous décrire votre démarche en matière de construction et de développement des personnages, notamment pour votre roman « Deepfake » ?

C’est une question qui mérite d’être posée. Pour « Deepfake », le processus a été très différent de celui des deux premiers romans de la trilogie : il a demandé plus de temps, et surtout bien plus de repérages. Le premier tome touchait à Athènes et à l’art contemporain, des domaines qui me sont familiers, donc l’alter ego s’imposait presque de lui-même. Pour le deuxième, le héros, Michalis Crocos, part en vacances à Ikaria, une île que je fréquente depuis toujours. Mais dans « Deepfake », le personnage infiltrait un groupe alt-right grec pour aider un ami ; cet univers m’était étranger. J’ai donc pris le temps de m’informer, d’explorer. Les personnages sont tous inspirés de gens de ma génération, adolescents dans les années 90, avec qui je partage une langue commune et des références culturelles. Pour la narration, j’ai privilégié le chaos, avec des scènes et des personnages secondaires qui semblent ne rien avoir en commun. Thomas Pynchon m’a fortement influencé, c’est l’un de mes modèles littéraires.

Votre série de « néo-polar », entre pulp et chronique sociale : comment planifiez-vous les différents volets ?

Au départ, il n’y avait aucun plan global — juste ce héros, « moi ». L’idée était une aventure unique. Mais il a survécu au récit, et les lecteurs se sont mis à demander : « Et après, que devient-il ? » J’ai compris qu’un univers s’était créé — presque le nôtre. Je me suis alors plongé entièrement dedans.

Quelle est votre routine de travail ? Cette méthode a-t-elle évolué avec le temps ou vous est-elle venue naturellement ?

Encore une fois, tout a changé avec « Deepfake ». Auparavant, ma routine était régulière et disciplinée : j’écrivais chaque matin de 8 h à 11 h, y compris dimanches et jours fériés. Avec ce livre, tout s’est effondré. J’ai commencé à travailler la nuit, dans mon lit, à des horaires discontinus… Peut-être que le thème du deepfake a même contaminé ma façon de créer.

Vous explorez des genres très variés : essai, roman, poésie, biographie. Adoptez-vous une méthode spécifique pour chacun ?

Non, pas spécialement. Si je suis convaincu que quelque chose peut fonctionner, je fonce.

Quel est le meilleur conseil qu’on vous ait donné en matière d’écriture ?

Que rien n’est gratuit, en littérature. Il faut savoir prendre des risques, même majeurs. Il faut payer. Ce conseil, je le dois à Céline.

Et à l’inverse, quel fut le pire conseil ?

(Rires.) Honnêtement, la plupart des conseils sont à jeter ! Comme « la réalité n’existe pas », ou cette idée étrange selon laquelle chaque phrase doit constamment exprimer un sens profond ou ce que « vous voulez dire ». Pour moi, une phrase doit être simple et porteuse de sens. Ensuite, le lecteur en fait ce qui lui plaît.

Quels sont vos principales inspirations ?

Au-delà de ceux que j’ai déjà cités : Hammett et Chandler, Manchette. Stevenson pour le souffle de l’aventure, souvent Kafka. John Fante est remarquable. Beaucoup d’auteurs de science-fiction aussi — Gibson, Spinrad. J’ai une vraie admiration pour Hunter S. Thompson et son approche gonzo. Et Philip K. Dick, pour tout ce qu’il représente.

You have studied art, does this first passion nourish your writing?

These passions developed in parallel and have certainly nourished each other. I’ve often found myself asking, in both visual arts and literature, «how did they do it?». How, in a tangible, technical sense, did the creator make me feel a certain way? Pursuing that question is how I began to understand the craft of writing.

Where does your inspiration start? What is the fire starter of a story? Do you take a lot of notes?

I don’t take any notes. My process is unorthodox one could say: a single draft, which is both the first and the final one. The story begins and develops in my mind; I remember everything and seldom go back to make changes. It usually starts with a simple idea, an odd event in the hero’s life. I take it from there, operating on the assumption that I know (or will learn through repérage) how the world works.

When you're developing a new story, what usually comes to you first — the theme or the characters?

The central character is a declared alter-ego, a writer trying to get published the book I wrote last. He gets into trouble, and that creates the premise for my current book (and his next one). So, the characters come first. The theme must be something that forces him out of his downtown nest, not necessarily a «comfortable» one, but a nest all the same. In that sense, the «theme» is the world itself.

How do you go about shaping the narrative? Could you walk us through your process in terms of structure and character development, especially for your selected novel « Deepfake » ?

That’s an interesting distinction. The process for «Deepfake» differed from the other two novels in the trilogy. It took more time, and most importantly, far more «repérage». The first book dealt with Athens and contemporary art, subjects I know well, so the alter ego system felt natural. The same was true for the second, where the hero, Michalis Crocos, goes on holiday to Ikaria, an island I know from family and frequent summer visits. For «Deepfake», however, the hero infiltrates a Greek Alt-Right group to save a friend, and my knowledge of that world was limited. I had to take my time to conduct significant repérage. The characters are all people I know, mostly from my generation, teenagers in the 1990s, with whom I share a common vernacular and cultural references. I wanted the narrative to feel chaotic, with seemingly unrelated sequences and side characters; a major influence was Thomas Pynchon, one of my literary heroes.

You have built a «neo polar» series, between pulp and social observation, how do you plan the different tomes of the serie?

There was no master plan initially — just that hero, «me». It was meant to be a one-shot adventure. But he somehow survived, and people began asking, «so, what did he do next?». I realized a universe had emerged, very close to our own, where this hero exists. So I dove deeply into that universe.

What does your typical working routine look like? Has this method evolved over time, or did it come to you naturally?

Again, things changed with «Deepfake». Until then, my routine was consistent and disciplined: I worked only from 8 to 11 every morning, Sundays and holidays included. With this book, my «system» fell apart. I began working at night, in bed, keeping irregular hours… Perhaps the theme of deepfake corroded the very making of the book.

You write in many different genres, essay, novels, poetry, biography. Do you have a specific writing routine or technique for each genre?

Not really. If I’m convinced something will work, I go on and do it.

What’s the best piece of writing advice you’ve ever received?

That nothing in writing is free. You must take risks, even great ones if necessary. That you have to pay. That came from Céline.

And on the flip side, what’s the worst piece of writing advice you’ve been given?

Haha! Mostly bad advice, honestly. Like that there is no such thing as «reality», or the strange idea that phrases must constanly reflect some inner meaning, what «you mean». I believe phrases should be simple and meaningful. Then the reader can do whatever the hell they want with them.

Who are your main and strongest inspirations?

Besides those already mentioned: Hammett and Chandler, Manchette. Stevenson for the high adventure, and often Franz Kafka. John Fante is absolutely great. Many science fiction writers too, like Gibson and Spinrad. I admire Hunter S.Thompson for his Gonzo process. And Philip K. Dick for everything.

![[INTERVIEW] Pierre Chavagné : "La Nature dans mon roman devient un personnage à part entière"](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/63bc3dced6941a828cf893ac/6938013865c7fbebfa2c0654_abena-pierre-chavagne-lemotetlereste.jpg)

![[INTERVIEW] Laura Lutard : " Soudain, le poème est impératif !"](https://cdn.prod.website-files.com/63bc3dced6941a828cf893ac/6932f7ad65a3c836e0d2d5dd_laura-lutard-nee-tissee.jpg)